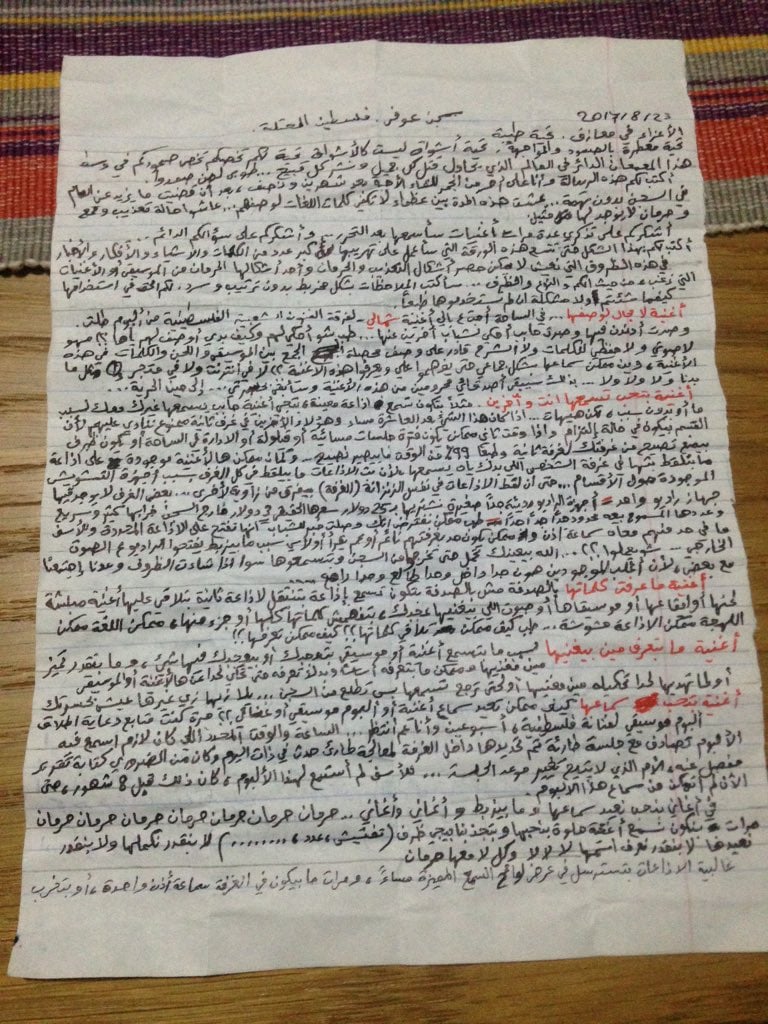

Hassan Karajah is a Palestinian activist from Safa, a village in the West Bank. In July of 2016, he was detained by the Israeli forces and spent a year and a half in prison without ever having been charged. He is one of the founders of the initiative “Tajwal Safar” (Wandering and Traveling), and the youth coordinator of a nationwide campaign against settlements and the wall of separation in the West Bank.

Ofer Prison, Occupied Palestinian Territories

August 23, 2017

To my dear friends at Ma3azef,

I send you my warmest greetings; greetings filled with resilience and resistance; greetings that express a yearning unlike any other yearning; special greetings in honor of your resilience amidst the ceaseless turmoil of this world, which seeks to destroy all that is beautiful so that the hideous may prevail. Blessed are those who have remained steadfast.

As I sit writing this letter, I am overcome with excitement in anticipation of my being reunited with my loved ones in two and a half months. I will have spent over a year in prison without ever having been charged. During this period, I have lived among people so great I have no words to describe them, people who have endured unimaginable torture, repression, and deprivation.

Thank you for reminding me time and again of some of my favorite songs, which I will listen to when I am released. And thank you for checking in on me time and again.

I am writing to you in this way so as to fit as many words, ideas, and tidings on this sheet of paper, which I will try to have smuggled out.

I couldn’t possibly list all the methods of torture and deprivation we experience here, but one of the ways in which they torture us is by depriving us of the music we love. I will record my observations as they come to me and without a structure or narrative. You are welcome to use them as you please—and of course it is perfectly alright if you choose not to use them at all.

On the Song You Cannot Describe

One day, while I was in the prison yard, I felt the urge to listen to the song “Shamaali” by the band El Funoun El Shaabiya El Filastiniya, from their album Tallat. I began humming the melody and wanted to tell the others about it. But what could I tell them? How could I describe it to them? Not my voice, nor my memory of the lyrics, nor a description of the song could possibly do justice to the interplay of music, melody, and lyrics. Where could we listen to the song together so that they could understand what I was talking about? There’s no internet, no music shop, nothing. Thus, my friends will remain deprived of that song and I will suffer all the more because of it. Until the day we are all set free.

On the Song You Would Like to Listen to Together with Others

Sometimes, when you’re listening to the radio, a song comes on that, for one reason or another, you think someone else might want to listen to. But this is wishful thinking. If this should occur after 10 PM, then we are no longer allowed to call people in the other cells. If it should happen at any other time, there is a high likelihood that it would be during evening gatherings, naps, or other times when we are being supervised and when it is forbidden to shout from one’s cell (which is about 99% of the time). It might also be the case that the song is playing on a station that cannot be reached from another part of the prison due to interference from the guards’ walkie-talkies. In some cells, they don’t even have a radio. The low quality radios we have cost us 25 dollars in prison, while they cost only three dollars on the outside.

If you should succeed in letting the others know that a particular song is being played on the radio, you should know that the other prisoners don’t have headphones, which means you cannot listen to the radio, as there may be others who are sleeping or reading. So what do you do? You wait until you’re out of prison to experience the joy of listening to music with others.

On the Song the Lyrics of Which You Can’t Make Out

A song comes on the radio. You like the music but can’t make out the words, either because of singer’s dialect or because of the poor sound quality. How will you ever find the lyrics?

On the Unknown Singer

A song comes on the radio. For one reason or another, the music or something else about the song pleases you. But you don’t recognize the voice, or maybe you don’t know the singer to begin with. You want to know who it is so that you can talk about it or recommend it to someone. Or maybe you’d like to listen to it when you get out of prison. Just like before, you’re left to suffer all the more because of it.

On the Song You’d Like to Listen to Again

How can you replay a song or an album you like? Once, I spent two weeks waiting for the release of an album by a Palestinian singer, news of which I had been following on the radio. On the day the album was released, we had to hold an emergency meeting in the cell to deal with a situation that had occurred that same morning, and we had to write a report about it, which made it impossible to reschedule the meeting. Sadly, it’s been eight months, and I still haven’t been able to listen to that album.

There are so many songs we’d like to listen to again. But it never works out. Songs upon songs. Deprivation deprivation deprivation deprivation deprivation deprivation deprivation.

Sometimes, we’ll be listening to a song we really love and something will happen (an inspection, a roll call, etc.) and we won’t be able to finish the song, or listen to it again, or even figure out what it’s called. No no no. Every ‘no’ carries with it another form of deprivation.

The radio stations usually play the best songs at night, but often you can’t find any headphones in the cell. Or the only headphones you have are broken (All of the electronic devices in the prison are of a poor quality and very expensive). Nights, usually a spiritual time, are when most administrative activities take place, making it difficult to borrow something from another inmate. Spontaneous inspections are an exception. In fact, some of the prisoners rejoice when an inspection occurs in the middle of the night, because it gives them an opportunity to see the moon – provided it has risen and there are no clouds covering it – as the jailers take the prisoners out into the yard. Anyway, let us get back to our topic. How can people enjoy themselves at night if there are no headphones? If the headphones are broken, how can they be repaired? At night, it’s impossible to listen to the radio out loud. The unspoken rules among the prisoners do not allow it. Everyone in the prison suffers enough during the day. We must also be considerate of the older prisoners. There is a man in my cell who is 72 years old, imprisoned indefinitely.

In the section of the prison in which I am held, there are members of the Popular Front and Hamas. Once, I was talking with some guys about alternative music. One of the Hamas militants overheard us and asked me what that was. I talked to him a bit and tried to explain it to him in the little bit of time we had. Then one day I saw that there was going to be a program on the television channel Al Arabiya about alternative music, featuring Emel Mathlouthi. I told the guy what time the program would be airing. Unfortunately, he didn’t end up watching it because there was a soap opera on at the very same time, which most of the guys in his cell wanted to watch. Because they are members of Hamas, they have little to no interest in subjects with no relationship to religion. For this reason, they were not willing to forgo the soap opera and watch a program on music about which they know nothing and which does not represent them. That guy ended up spending another eight months there, and in those eight months, he never had another opportunity to learn the truth about alternative music, or even to learn to recognize it, should he one day happen to hear some.

In prison, we have three sources of music: radio, television, and CD players. The television channels are as follows: MBC, MBC Drama, Channel 3, RT, National Geographic, and Al Arabiya. As for CD players, there are two in our section of the prison, which has 120 inmates. Both are of a very poor quality. The albums we are allowed to purchase are very, very, very limited. Every year, no more than ten albums enter the prison. All of them are either very old or commercial productions. It goes without saying that they are very expensive and are quickly damaged, for no apparent reason.

There is no end to the deprivation inflicted upon us in the prison. I am certain that I have forgotten to mention countless details that would pain you to learn. A great many of the prisoners are not concerned with such things, because their priorities lie elsewhere: medical negligence, mattresses, blankets, food, ill-treatment, unjust sentences, and lengthy incarceration periods.

The prison might best be described as a “living cemetery.” It is a feeling that would be difficult for someone to understand without having experienced it for himself – something I wouldn’t wish upon anyone. When Thameena told me that Ma3azef had dedicated a song to me, I felt at once overcome with joy and with sadness: joy because of the support and sadness because I was being deprived of music. I was also bewildered. What song was it? What did it sound like? What about the melodies and harmonies? How could I know without hearing it?

I have no words to describe how much I long to listen to the songs on Thameena’s SoundCloud, no words to express how much I want to get out of here and continue working on the music education project that I started with Thameena in our village, a music school that will offer something to humanity.

Once, when the visitation period had just ended and Thameena was about to leave, I had the urge to tell her to listen to a particular song. But how could I tell her the name of the song with a glass barrier between us? It’s forbidden to bring a pen or paper to a visitation, or anything else for that matter. Thameena left and I returned to my section of the prison without having told her about the song. What kind of person designs such prisons!?

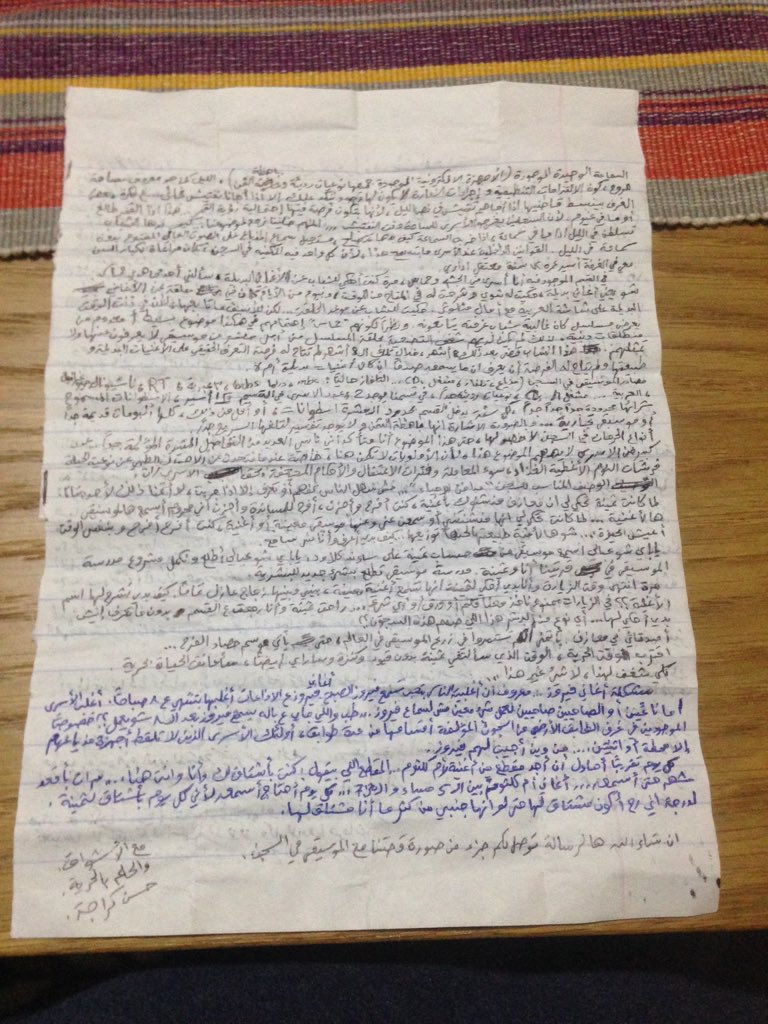

My friends at Ma3azef: I hope you will continue to sow music in this world until the season arrives when we can harvest all that happiness. Freedom is near. Soon, I will again be together with Thameena, unshackled, and I will embrace liberty. That’s all I want. That’s all.

The problem with Fairuz. It’s well known that most people like listening to Fairuz in the morning. Most radio stations stop playing Fairuz’s songs by 8 A.M., a time when most prisoners are either asleep or have woken up to do something in particular (not to listen to Fairuz). What is one supposed to do when one feels like listening to Fairuz after 8 A.M.? Especially those prisoners who live on the ground floor of the prison – which is several stories high – those prisoners whose radios receive just one or two stations. How can I bring them Fairuz?

Just about every day, I try to find a part of a song by Umm Kulthoum, the part where she says: “I was missing you while you and I were together.” Sometimes I go a month without hearing it. Umm Kulthoum’s songs are played from 5 to 7:30 in the evening. Every day, I feel a need to listen to them, because every day I miss Thameena, so much so that I would miss her even if she were right here beside me.

I hope this letter gives you some idea of our relationship with music here in prison.

With love,

And dreaming of freedom,

Hassan Karajah

Photographs of the letter are below. The original Arabic letter can be found here.