The Arabic Music Exhibition in Paris | A Convergence of Kitsch and Orientalism

معازف ۱٤/۰٦/۲۰۱۸

Original article by Fadi Abdallah | 09/05/2018

Translated by Farah Zahra

The exhibition Al Musiqa, on view at the Philharmonie de Paris through the middle of August, was not born of bad intentions. For one thing, it reflects an awareness on the part of the organizers that Arabic music is not alien, that it has long been a part of the musical tapestry of the west, from the music of Andalusia all the way up to Raï. Moreover, the organizers were no doubt aware that this year marks the thirtieth anniversary of Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism, and felt it was thus necessary to include texts from Arab contributors, and to show respect for and a willingness to take seriously their musical traditions. There were several other good ideas, such as creating a special exhibition for children and incorporating works by contemporary Arab artists with music or another of the exhibition’s topics as their themes.

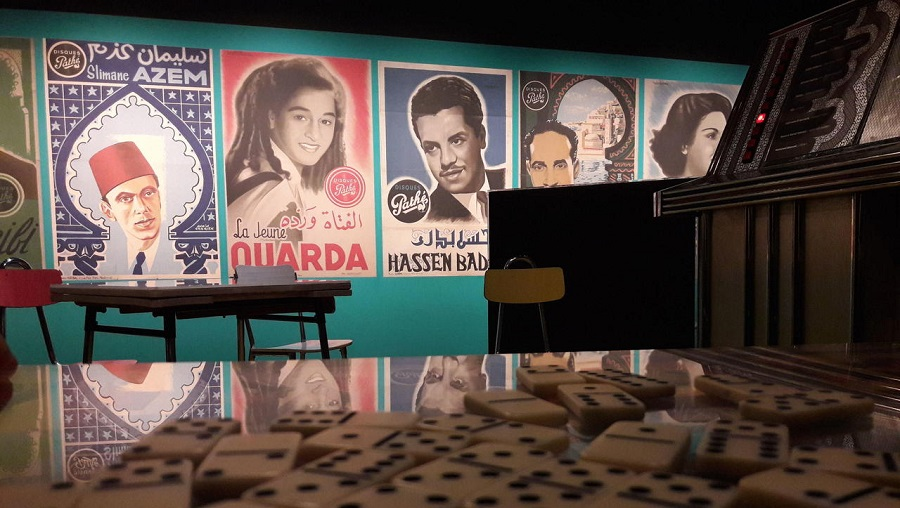

Nevertheless, the road to hell is paved with good intentions – as the French themselves like to say. The exhibition contained an unprecedented amount of kitsch, of a greater quantity and symbolic importance than what one would typically find in such an exhibition: first, the watercolors and orientalist designs (the tent, the loudspeaker – mounted on top of a structure vaguely resembling a minaret); next, the fez hats scattered throughout, the cans of Nido, tomato paste, and Luncheon all over the place; and last, the papers dotted with eight-pointed stars and the suggestion that children use zellige tiles and model domes as toy building materials (like finding, in an exhibition about British music, children building a model of London using gothic arches and roman columns rather than glass skyscrapers). Whatever the intended message of the exhibition’s organizers may have been, all that is Arab is nevertheless represented, at least visually, as both “other” and “ancient,” a depiction with which we have long been familiar.

In addition to the exhibition’s technical weaknesses (it was, for example, necessary to plug headphones into the walls in order to be able to listen to the audio clips) and the short supply of meaningful content (no rare recordings or manuscripts, save for a very small number, no precious musical instruments, save for an oud, built in 1931 by the luthier George Nahhat, a solitary and rather recent example), the exhibition and its organizers – whether Arab or French – appear confused about their content on many levels.

The first problem concerns the relationship between Islam and Arab identity. It seems the exhibition’s organizers did not read what the contributor Abdul Rauf Ortani wrote for the exhibition itself, namely that Arab ‘musics’ cannot be defined as an expression of Islam. Upon entering the exhibition, one comes face to face with a timeline depicting the history of the Arabs, which unfolds across 25 stages, beginning with the prophet of Islam, and moving on to topics such as pre-Islamic poetry, the practice of singing to camels, and the religious music of the Umayyads and Abbasids. However, when the exhibition discusses the influences on Arabic music at the time, all that is mentioned is the influence of the Persians and Ethiopians – and, later, in a discussion of Sufism (which is presented as a bizarre and inscrutable set of practices), the influence of Sub-Saharan African music. In other words, the exhibition’s organizers make no mention of the fact that what is today called Arab music (the plural “musics” is more fitting here, as it expresses the great variety Ortani refers to) is the music, or musics, of all those people who live in countries that today identify as Arab, people whose history did not begin with the birth of Islam in the Hejaz. In doing so, the organizers disregard the cultural inheritance of the Levantine/Byzantine, Egyptian/Coptic, Mesopotamian, and Maghrebi/Berber civilizations, which preceded the genesis of Islam by thousands of years, influences that, to this day, have not disappeared from these peoples’ musics. After all, music is not like language. It carries on even when the languages of new rulers are adopted. The Arabization of the liturgy of the Oriental Churches is but one fairly straightforward example of this. So too is the practice of Egyptian Jews of translating Jewish religious songs from Hebrew into Arabic and setting them to music that is in no way different from any other Egyptian music (take, for example, Zaki Efendi Murad singing in Arabic).

The second problem concerns the exhibition’s being a French enterprise. The visitor is left with the impression that what most interested the organizers was the situation of Moroccans and Algerians living in France and how this situation is treated in their music. The topic allotted the most space was the music of the Arab diaspora. This was, however, limited entirely to Arabs living in France. There was no trace, for instance, of the recordings made by Arabs in Brazil and the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, or of any other such communities in Spain, England, etc. Ultimately, what had interested the organizers were the Moroccans and Algerians living in the Barbès neighborhood of Paris, the salons they established, and the popularity of those salons during and after the wars for independence. Cheb Khaled and Bachar Mar-Khalifé – the son of Marcel Khalifé – are presented as representing France on the global stage (as if this were the World Cup). While the organizers obviously have the right to address the Arab diasporas living in France – it is, after all, an exhibition in Paris – in limiting its scope to such an extent, they leave out far too much. Ultimately, the exhibition begins to take on an overtly political tone, far from the positioning of the organizers, who present themselves as impartial intellectuals.

Unsurprisingly, the third problem concerns the issue of Orientalism and of the organizers’ including Arab writers in the service of an Orientalist vision that contradicts the organizers’ own statements about the project, which they describe as a decidedly non-Orientalist undertaking. The Arab and non-Arab contributors are indistinguishable in their absurdly Orientalist viewpoints and in their oversimplifications, both surprising and unacceptable. For an idea of what I’m talking about, let us compare the differences between the Arabic, French, and English texts, which are widespread and at times dangerous. Where the French and English versions of a text talk about the presence of important “melodic elements” in Islam, the call to prayer, and Qur’anic recitation, the Arabic version talks about the importance of “composition” (!). Meanwhile, the contributor Anis Fariji, in what is ostensibly an overview of contemporary Arabic music, chooses to focus exclusively on two composers, Zad Moultaka and Ahmad Al-Sayyed, and their viewpoints, disregarding innumerable composers who have taken their music in different directions. The problems continue in matters of linguistic and historical accuracy. Take, for example, the exhibition’s director, Véronique Rieffel, who mistakenly claims that the Cairo Congress of Arabic Music was held in 1922, when it was in fact held in 1932, long after the revolution of 1919, when Egypt declared itself independent from the Ottoman empire.

Absurd statements and superficial, kitschy writing abound, from contributors both French and Arab. Christian Bouché seems to have been competing with himself in contributing both a dimwitted article about singing camels – in which he draws on stories by Orientalists and compares Arabic singing with the sounds of camels – and other, unsubstantiated, stories about the first taxi rides between Damascus and Aleppo and the songs of Umm Kulthoum, one of which, he claims, lasted for four hours. At one point the contributor Nadia Muflih contends that Samia Gamal was both a singer and a dancer, and that Abd Al-Halim was described as the Sinatra of the Nile, when that is widely known to have been the sad-faced crooner Farid Al-Atrash.

Although the short format of the articles, of which there were very many, prevented contributers from presenting a wide range of rich ideas, these factors are no excuse for oversimplification, as is evidenced by two instances of contributers actually succeeding in adding something meaningful to the discussion. One, Jean Lambert, writes about the Arabic Music Congress of 1932, which saw the replacement of the term “Eastern Music” through “Arabic Music.” He then writes about the relationship between political developments, the project of constructing an Arab identity, and the desire of Egyptian and other Arab musicians to distance themselves from the Ottoman traditions while at the same time preserving Ottoman instrumental compositions and integrating these into the Arabic poetic tradition. This development shocked foreign ethnomusicologists, who were concerned with preserving and recording traditional music in its original forms. Another successful contribution comes from Abdul Rauf Al Ortani, who explains that neither Islam, nor the Arabic language, nor the Arabic modal system is sufficient for defining Arabic music, which covers a geographical area with a wide variety of religions, peoples, and musical forms. He concludes with a point similar to Lambert’s analysis of the Arabic Music Congress, namely that the creation of the term “Arabic Music” is itself an expression of “a desire to construct an Arab identity,” and of the political, historical, and geographic context of this desire. Accordingly, the question is not one of Arabic music per se. Rather, it is a question of who decides whether any given music is “Arabic” or not.

At the end of the exhibition, Rieffel, the exhibition’s director, thanks a great many of friends and contributers. A quick glance at the list of names reveals that a considerable number of them are Arabs. Nevertheless, this does not make the exhibition a “view from within,” nor does it make it immune to kitsch (in its visual form, as it is commonly understood to mean) or Orientalism – and most certainly not from their convergence!